- Published on

Converting a 64-bit integer to a 32-bit float

- Authors

- Name

- Timothy Herchen

A silly little thing that I've encountered 3 times now (!) is converting 64-bit integers to 32-bit floats in JavaScript.1 In most languages that'd just be a cast, but in JavaScript, a language decidedly not like the other girls, the answer is a bit tricky.

To be more specific, we want to provide a function of the form:

function l2f(val: bigint): number;

which takes in a bigint between and and converts it to the nearest 32-bit float. If there is a tie between two float values, the one with a 0 in the mantissa's last place will be chosen – this is called "rounding to even".

The straightforward approach is to first convert to 64-bit double, then convert to 32 bit:

function l2f(val: bigint): number {

return Math.fround(Number(val));

}

(Math.fround is a built-in JavaScript function which converts 64-bit doubles to 32-bit floats.) This works for the vast majority of inputs, but there are some exceptions. The problem is that even though doubles have more precision than floats, they still only have 53 mantissa bits, which is less than 64. Therefore, the initial conversion (to double) potentially loses information that would influence the second conversion (to float).

A counterexample

Consider the number , written out in binary below:

I've marked where the rounding will occur for floats (24 significant bits) and doubles (53). For floats, the rounded-off portion – which I've highlighted in blue – is :

Evidently, the rounded-off portion is slightly closer to 0 than to 1, so we round toward 0 and obtain:

which corresponds to the float . (interactive viewer)

This is the result you'll get from Java, C++, Rust, etc. – but our JavaScript solution rounds to double first! In this conversion, the rounded-off part is now , which is closer to 1 than to 0:

So we round up!

Then we round this double to a float. The rounded-off part is exactly 0.5, so we consult the last significant mantissa bit (highlighted in red below) to determine which way to round.

Because it's 1, we round up, which will make it zero again. (Again, this is "ties to even". If it were 0, we'd round down.)

This corresponds to the float ... which is wrong indeed.

Devising a correct implementation

The most straightforward solution, perhaps, is to do some bit twiddling with typed arrays and implement the rounding yourself... but that's no fun. The fun solution is to round the intermediate result to odd, which is a common technique when emulating lower precision with higher precision (Boldo & Melquiond, 2008).

The intuition here is that for the intermediate result, we care more about the ultimate rounding direction than to get the closest value right off the bat. Therefore, if there are any nonzero bits rounded off, we round in whichever direction will make the last mantissa bit a 1. It's a "sticky bit" of sorts.

Consider the example we gave above.

Previously, we got screwed over after rounding up the intermediate double; but now, because the last mantissa bit is a 1, we actually round down, i.e., truncate the bits. Thus the last bit stays odd.

The final rounding is now in the correct direction (down):

Here's another example, , where rounding to odd has us first round up instead of down:

which preserves the fact that this isn't a tie for 32-bit floats, and we need to round up:

This is the smallest positive example; in general, of 64-bit numbers have this problem.2

Implementation in JavaScript

The remaining question is how to implement the rounding to odd, especially in a language like JavaScript where we don't have access to the FPU environment. For example, glibc's fallback implementation of fmaf uses it twice: first to temporarily set the rounding mode to round down and clear the inexact flag, and second to check the inexact flag.

We can't set the rounding mode, but we can use the default (rounds to nearest) rounding and then check the direction of the error by comparing BigInt(Number(val)) and val. Restricting to positive values for a moment, the case work is:

- Conversion was exact: no additional work to do.

- Conversion was inexact?

- If the last mantissa bit is 1: no additional work to do.

- If the last mantissa bit is 0 and we rounded up, subtract one ulp to undo the effect.

- If the last mantissa bit is 0 and we rounded down, add one ulp to round to odd.

Let f = Number(val). We can compute an ulp using u = (f * (Number.EPSILON / 2) - f) + f (the order of operations is important), and check the last bit of the mantissa by subtracting u/2 and taking advantage of ties-to-even; if f == f - u/2 then the last mantissa bit is 0. (By construction, u and f have the same sign.)

So here's a complete and fairly compact solution which works for all values, including negative ones:

function l2f(val: bigint): number {

let f = Number(val);

const rounded = BigInt(f);

const ulpTowardZero = f * (Number.EPSILON / 2) - f + f;

if (rounded !== val && f - 0.5 * ulpTowardZero === f)

f += rounded > val !== val < 0 ? -ulpTowardZero : ulpTowardZero; // (*)

return Math.fround(f);

}

An astute reader might notice that the analysis is sloppy for val near powers of two; e.g., if f is then u is , while the predecessor and successor of f are and (not a typo!). Then (*) wouldn't work for adjusting the final value. Indeed, this would be a problem if we were ultimately trying to do a directed rounding; but since we're doing rounding to nearest, any input sufficiently close to a power of two won't be close to an single-precision tie, and we'll still get the correct result despite not rounding to odd.3

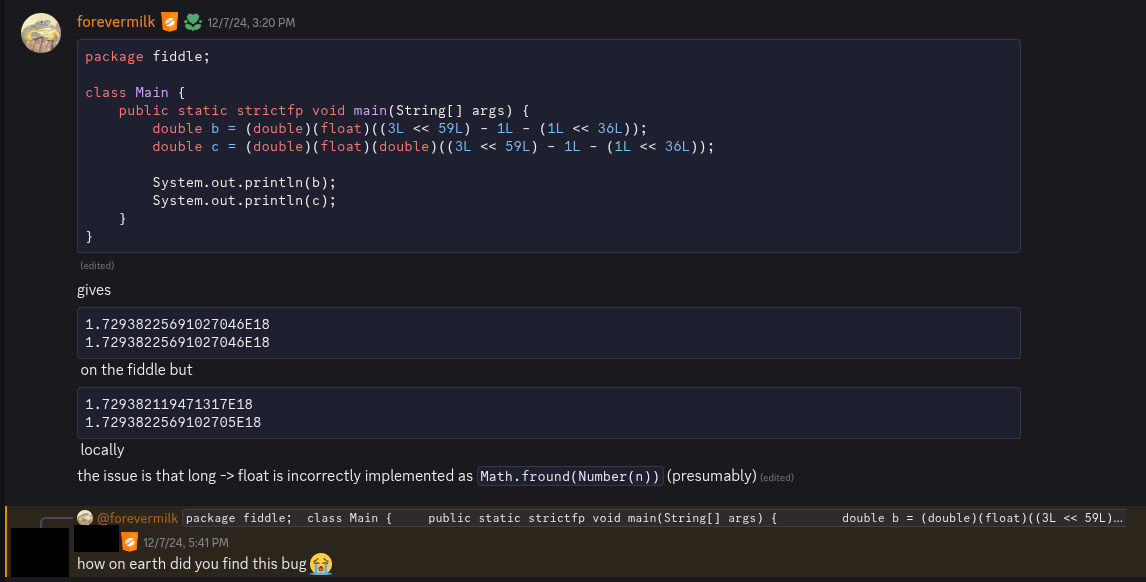

In the wild

I pointed out this bug in the Discord of a JVM implemented in JavaScript. I'll end off with one of the funny reactions:

AI disclosure

No generative AI was used in the creation of this post.

Footnotes

Rather than this problem being common in general, I think this is more a reflection of my frequently working at the intersection of compilers and webdev. ↩

Getting the exact number is a somewhat annoying but straightforward counting exercise. I won't publish it here, because I use it as an LLM benchmark. ;) ↩

But you can modify this function to work for directed rounding, by scaling the addend at

(*)by some value slightly greater than 1. ↩